I get annoyed when conductors hold up two or four fingers as they start beating a passage to let me know whether they’re beating the time in halves or quarters. If you conduct clearly it’s obvious. If you don’t then by the time I see your fingers and process what it means I’ve probably gone double or half speed already. It reminds me of the road signs in Dover (a port in south-east England): for about a mile after you drive off the ferry they are telling you, in four languages, to ‘Drive on left’. How many accidents do they reckon this saves? If you haven’t figured this out by the time you’ve driven a mile, it’s probably a bit late, no?

Showing posts with label conducting. Show all posts

Showing posts with label conducting. Show all posts

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

How not to phrase

My current obsession is phrasing. I hardly ever hear it done the way I think it should be. Here are some of the things people seem to think.

- Every time you see a slur or phrase mark, you have to put a big accent at the beginning of it. This is especially true if you are a string player taking a down-bow.

- When you have two slurred notes, you always have to do a massive diminuendo from the first to the second, and the second should be very short.

- You should never make one long phrase when you can make four shorter ones, and you should emphasise this by making the last note of every phrase very short.

- If you have a syncopation that accentuates a weak part of the bar you should emphasise this by playing the strong beat beforehand very weakly and then putting a massive accent on the syncopated note.

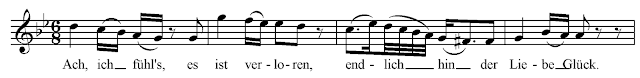

This is obviously all complete nonsense. Instrumentalists should think of how their line would look if it belonged to a singer. Consider the first line of Pamina’s aria, ‘Ach, ich fühl’s’, from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte.

Now this is from memory so I hope you’ll be kind if the last note is really a quarter rather than an eighth, or similar, but this is about how it goes. The German roughly means: ‘Ah, I sense it, it is lost, forever gone love’s happiness’. Pamina sings this aria when Tamino, who has been told by the priests that he will lose Pamina forever if he speaks to her, refuses to answer her, and she takes it as a sign that he no longer loves her.

Here is what you would get if you put this line, without text, in front of most orchestral players:

Now you will not find any soprano in the world who will sing the line like this – at least not one who understands the text or has the remotest clue about how to sing – because it wouldn’t make any sense. It’s one sentence and needs to be phrased with as much line as possible, especially in the slow tempo, so that we understand it as such. And every time instrumentalists see one of these slurs they should remember that it represents one syllable carried over two or more notes. Not even a whole word, let alone a whole phrase. But go into any classical concert and I promise you will hear this kind of phrasing all the time.

I wonder where it comes from. I think it might be bad teachers with nothing to say about the music. It’s a very easy, superficial way of telling the pupil how to ‘improve’ their performance to look down at the page, see a few slurs, accents and syncopations, and tell the poor unsuspecting student ‘you have to emphasise all these things or it’s boring’. After five hours of teaching, often working on music that you might not know all that well, it can be hard to find profound insights. Maybe you are a master of your instrument and good at sorting out people’s technique but not so hot on interpretation. Perhaps your student isn’t really that amazing either, or hasn’t done enough practice, and your motivation is waning. Maybe in some conservatories it is even true that in order to show the jury at your performance exam that you have noticed the slur or the accent you have to parody it. But whatever the reason, it is now incredibly hard to impress on orchestral musicians that it is possible to play the long phrase and let the details speak for themselves.

And even singers, though they might be a bit less inclined to completely bomb a phrase’s meaning to the ground, are also more and more inclined only to sing properly on the strong syllables. I am constantly reminding singers during coachings that the weak syllables have to be looked after as well. It’s very hard to understand a sentence of text where only the strong syllables are projected.

Has anyone got any other ideas where this might come from? Does anyone else find it as annoying and unmusical as I do?

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

How to wind an orchestra up in a first rehearsal

Actually there are quite a few ways. One really good one, though, is to stop every eleven bars to say something uninspiring about playing the staccatos shorter, starting the crescendos quieter, using softer sticks for the timpani, or any of the other dozens of things that good musicians will figure out for themselves once they've got a bit of an overview.

You do this mostly to cover up for having stopped because it fell apart due to your lack of clarity; not daring to draw attention to this by either apologising or attempting to blame the players, you try to act like you stopped for something else. Already made uncomfortable by this failure, you start to obsess that the players are watching you like hawks and noticing your ineptitude with the grim relish of a connoisseur sending back corked wine, which they are. Never all that secure about your conducting to begin with, this latest confirmation of your self-doubt makes you unable to do the simplest thing; you can't give a clear upbeat and even if you do you aren't sure the tempo you hear is the one you meant, or if the one you meant was even right anyway, and maybe the orchestra misread you because they have a different tempo in their heads, and maybe in fact they're right and you were imagining it wrong, and all this self-analysis when you should be concentrating on listening to the rehearsal makes you lose concentration and you realise you've had to stop again, but you were so busy thinking about what had gone wrong with the upbeat that you haven't been listening and can't think of anything to correct, and you look down at the score trying to find a commonplace mistake that you weren't sure if it was wrong but somebody probably did play it wrong somewhere and even if they didn't they might do next time, and on you go, making it worse and worse. And you can practically hear them asking each other, 'why is this guy conducting us', and well, hell, why wouldn't you hear it, everyone else can. As you pick a place to start two bars further forward than the previous time so it feels like you're making progress and count out the measures for the orchestra, you see out of the corner of your eye that the normally docile woodwind players are exchanging looks, and you try to tell yourself it's a private joke that has nothing to do with this rehearsal but you remember your own days playing in an orchestra and you know that isn't true.

Well, we've all been there, conductors and players alike, and knowing what it feels like from the other side I have more sympathy than it sounds like just now. But although the reasons outlined above account for most of the first-rehearsal stopping, and actually most conductors doing this know perfectly well that the most productive thing would be to crash through with only the most critical stops, they do still sometimes forget that and manage to convince themselves that talking to the orchestra is useful. Orchestral players know that it isn't. And it certainly isn't when the players haven't got any idea of the music yet. Why not?

It seems to me that we are wired up to learn music (and other things) in a way that resembles the appearance of a Google Maps image loading on a slow smartphone. Very blurry at first, then kind of pixellated with some patches of green visible, then suddenly the hit of satisfaction as the image rights itself and sharpens up. And you know also how while it's loading the phone is apt to freeze if you try to drag the map an inch or two to the side, but once it's got the area loaded into the memory you can drag, zoom in, zoom out, search for the closest place to buy charcoal or display all the bus stops served by night buses and the phone will keep up with your impatient fingers, gliding effortlessly through hyperinformatic space. (If you're reading this in a couple of years' time and can't believe people used to struggle through life with technology this deficient, imagine how I feel.)

So, but this is what learning music is like. You can't find the shortest route from ATM to off-licence until you've got the whole picture loaded. It is most especially not like pictures used to download in early versions of Netscape c. 1992, a beautifully defined strip of sky, followed by a perfect treetop, eventually a few strands of hair at the top of the tallest person in the picture's head, and an eternity later, legs, feet, ground. (Probably what changed this is that the men writing the software for these browsers thought about the kind of pictures they most often wanted to look at on the internet and realised it was not in their interests to spend their then-precious bandwidth allowances on the detailed image of people's head-tops before you knew whether you liked what you were getting much lower down in the picture.) Music cannot be learned this way. You can only get to the detail by going through the overview; you just need to play something through a few times, eventually things start to click into place. Conductors who understand this and just let you play get results much faster.

It's getting late and I have another rehearsal to look forward to tomorrow morning so I have to stop writing pretty soon but just one further thought. I'm sure you know what I'm talking about whether or not you're a musician; we've all experienced that feeling of not really knowing enough about something to make any connections, the sense that reading another article on the same topic will just double your overall understanding of it from nothing to nothing, the questioning whether you will every really actually get the thing enough to really be comfortable with it like other people seem to be. But equally you will know what I mean that at some point things just click somehow and it all does make sense, and not only does the next thing someone tells you about the topic seem to make complete sense, but it connects with something else you remember hearing about it that at the time you thought wasn't going in at all because it didn't really seem to mean anything, and then someone asks you to explain it to them and all of a sudden you find that you are doing that and sounding rather well-informed.

Well but then the brain must be able to store an incredible amount of not-yet-connected pre-knowledge long before it's in a position to make sense of it. That feeling you get when you listen to a piece of music for the twelfth time and you can hear what phrase is going to come next before it does, even if someone turned the player off, it only comes after quite a few playings. After the first time - with hard music, anyway - you would not be able to complete any phrases like that, or remember any of how the music goes 15 minutes after listening to it. You feel just as if you'd never heard it at all. And yet something has just remained, because you are still one-twelfth of the way to the point where you will be hearing it, and after the second time - when you still may not be able to remember how any of it goes - you will be one-sixth. I find this incredible. I do not find it difficult to accept that my brain can store a lot of information that I have access to and can marshall in a conscious way. But that my brain can also be storing a whole load of information that I can't get at and can't in any way sense is there, but that will at some point with the right sensory inputs be movable into this active conscious domain - I find that amazing.

You do this mostly to cover up for having stopped because it fell apart due to your lack of clarity; not daring to draw attention to this by either apologising or attempting to blame the players, you try to act like you stopped for something else. Already made uncomfortable by this failure, you start to obsess that the players are watching you like hawks and noticing your ineptitude with the grim relish of a connoisseur sending back corked wine, which they are. Never all that secure about your conducting to begin with, this latest confirmation of your self-doubt makes you unable to do the simplest thing; you can't give a clear upbeat and even if you do you aren't sure the tempo you hear is the one you meant, or if the one you meant was even right anyway, and maybe the orchestra misread you because they have a different tempo in their heads, and maybe in fact they're right and you were imagining it wrong, and all this self-analysis when you should be concentrating on listening to the rehearsal makes you lose concentration and you realise you've had to stop again, but you were so busy thinking about what had gone wrong with the upbeat that you haven't been listening and can't think of anything to correct, and you look down at the score trying to find a commonplace mistake that you weren't sure if it was wrong but somebody probably did play it wrong somewhere and even if they didn't they might do next time, and on you go, making it worse and worse. And you can practically hear them asking each other, 'why is this guy conducting us', and well, hell, why wouldn't you hear it, everyone else can. As you pick a place to start two bars further forward than the previous time so it feels like you're making progress and count out the measures for the orchestra, you see out of the corner of your eye that the normally docile woodwind players are exchanging looks, and you try to tell yourself it's a private joke that has nothing to do with this rehearsal but you remember your own days playing in an orchestra and you know that isn't true.

Well, we've all been there, conductors and players alike, and knowing what it feels like from the other side I have more sympathy than it sounds like just now. But although the reasons outlined above account for most of the first-rehearsal stopping, and actually most conductors doing this know perfectly well that the most productive thing would be to crash through with only the most critical stops, they do still sometimes forget that and manage to convince themselves that talking to the orchestra is useful. Orchestral players know that it isn't. And it certainly isn't when the players haven't got any idea of the music yet. Why not?

It seems to me that we are wired up to learn music (and other things) in a way that resembles the appearance of a Google Maps image loading on a slow smartphone. Very blurry at first, then kind of pixellated with some patches of green visible, then suddenly the hit of satisfaction as the image rights itself and sharpens up. And you know also how while it's loading the phone is apt to freeze if you try to drag the map an inch or two to the side, but once it's got the area loaded into the memory you can drag, zoom in, zoom out, search for the closest place to buy charcoal or display all the bus stops served by night buses and the phone will keep up with your impatient fingers, gliding effortlessly through hyperinformatic space. (If you're reading this in a couple of years' time and can't believe people used to struggle through life with technology this deficient, imagine how I feel.)

So, but this is what learning music is like. You can't find the shortest route from ATM to off-licence until you've got the whole picture loaded. It is most especially not like pictures used to download in early versions of Netscape c. 1992, a beautifully defined strip of sky, followed by a perfect treetop, eventually a few strands of hair at the top of the tallest person in the picture's head, and an eternity later, legs, feet, ground. (Probably what changed this is that the men writing the software for these browsers thought about the kind of pictures they most often wanted to look at on the internet and realised it was not in their interests to spend their then-precious bandwidth allowances on the detailed image of people's head-tops before you knew whether you liked what you were getting much lower down in the picture.) Music cannot be learned this way. You can only get to the detail by going through the overview; you just need to play something through a few times, eventually things start to click into place. Conductors who understand this and just let you play get results much faster.

It's getting late and I have another rehearsal to look forward to tomorrow morning so I have to stop writing pretty soon but just one further thought. I'm sure you know what I'm talking about whether or not you're a musician; we've all experienced that feeling of not really knowing enough about something to make any connections, the sense that reading another article on the same topic will just double your overall understanding of it from nothing to nothing, the questioning whether you will every really actually get the thing enough to really be comfortable with it like other people seem to be. But equally you will know what I mean that at some point things just click somehow and it all does make sense, and not only does the next thing someone tells you about the topic seem to make complete sense, but it connects with something else you remember hearing about it that at the time you thought wasn't going in at all because it didn't really seem to mean anything, and then someone asks you to explain it to them and all of a sudden you find that you are doing that and sounding rather well-informed.

Well but then the brain must be able to store an incredible amount of not-yet-connected pre-knowledge long before it's in a position to make sense of it. That feeling you get when you listen to a piece of music for the twelfth time and you can hear what phrase is going to come next before it does, even if someone turned the player off, it only comes after quite a few playings. After the first time - with hard music, anyway - you would not be able to complete any phrases like that, or remember any of how the music goes 15 minutes after listening to it. You feel just as if you'd never heard it at all. And yet something has just remained, because you are still one-twelfth of the way to the point where you will be hearing it, and after the second time - when you still may not be able to remember how any of it goes - you will be one-sixth. I find this incredible. I do not find it difficult to accept that my brain can store a lot of information that I have access to and can marshall in a conscious way. But that my brain can also be storing a whole load of information that I can't get at and can't in any way sense is there, but that will at some point with the right sensory inputs be movable into this active conscious domain - I find that amazing.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Too easy for children, too hard for adults

If you spend any time working in the music profession you are fairly sure to encounter a sage who will tell you, in the same kind of tones that people use to tell you the tea has more caffeine than coffee, that you may think Mozart is the easiest music, but really it's the hardest. The title of this post is what the great pianist Artur Schnabel said about Mozart's piano sonatas, and we all know what he means. Mozart's music is superficially pleasing to the unquestioning listener and, a little learning being a dangerous thing, one may dismiss it as facile and uninteresting before one has the emotional maturity to appreciate the depth of beauty and the understanding of the human spirit it contains. I went through this phase and lots of people do. Some never emerge, and they are probably the most legimitate targets of the waggish wisdom I describe above.

What makes Mozart harder than Brahms is that it is underspecified. The page of music contains few instructions aside from the notes. Unlike much romantic music - particularly opera (one page of La Bohème contains more slow down/speed up instructions than the whole of the Marriage of Figaro) - the score is not a recipe whose instructions you can simply follow, add water, stir, bingo. You have to figure out for yourself what is going to make the music come alive. So some adduce from that that this makes it easy to conduct Puccini, because you can make it sound like the piece the composer composed without making any decisions for yourself.

Well, to a point, perhaps. But it depends on the individual; most of us probably find it easiest to perform the music we best understand and feel the deepest connection to. For me, that is Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Britten, Shostakovich... others too, but not (or at least not yet) Puccini, Brahms, Wagner, Strauß. I plan on getting to them later in my career, but right now I'm quite sure that I know how a Mozart phrase is meant to sound (and am perpetually driven crazy by the fact that I believe hardly anyone else does - more on this in a later post). With Puccini I don't know just from looking at the page and seeing all those rits and accels what the phrase means; if I listen to a couple of recordings I might think, oh, right, of course, that's what he means - but if you need to get it from a recording that isn't really the best start for conducting it yourself. Sometimes people think it's just obvious that it goes a certain way and they think they've always known that but they've forgotten they learnt how it went from other people's interpretations. (There is nothing wrong with this, of course. The aural tradition is important. But I generally feel it's purer to get a feeling for the music from the printed page first - you can always go to the recording later. In an ideal world, this is; when learning music in a hurry, recording submersion is a strategy I often use. Again, more on this later.)

The point I'm making is that for me, right now, Mozart most definitely is easier than Brahms. I've had older people (mostly people who didn't know quite as much about music as they thought they did) say exactly that to me - 'ah, you want to conduct Mozart because you think it is easy, you don't realise how hard it is' and I wish now that I'd resisted that more vigorously. I should have said: it's precisely because I appreciate what makes it hard that I can do it.

What makes Mozart harder than Brahms is that it is underspecified. The page of music contains few instructions aside from the notes. Unlike much romantic music - particularly opera (one page of La Bohème contains more slow down/speed up instructions than the whole of the Marriage of Figaro) - the score is not a recipe whose instructions you can simply follow, add water, stir, bingo. You have to figure out for yourself what is going to make the music come alive. So some adduce from that that this makes it easy to conduct Puccini, because you can make it sound like the piece the composer composed without making any decisions for yourself.

Well, to a point, perhaps. But it depends on the individual; most of us probably find it easiest to perform the music we best understand and feel the deepest connection to. For me, that is Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Britten, Shostakovich... others too, but not (or at least not yet) Puccini, Brahms, Wagner, Strauß. I plan on getting to them later in my career, but right now I'm quite sure that I know how a Mozart phrase is meant to sound (and am perpetually driven crazy by the fact that I believe hardly anyone else does - more on this in a later post). With Puccini I don't know just from looking at the page and seeing all those rits and accels what the phrase means; if I listen to a couple of recordings I might think, oh, right, of course, that's what he means - but if you need to get it from a recording that isn't really the best start for conducting it yourself. Sometimes people think it's just obvious that it goes a certain way and they think they've always known that but they've forgotten they learnt how it went from other people's interpretations. (There is nothing wrong with this, of course. The aural tradition is important. But I generally feel it's purer to get a feeling for the music from the printed page first - you can always go to the recording later. In an ideal world, this is; when learning music in a hurry, recording submersion is a strategy I often use. Again, more on this later.)

The point I'm making is that for me, right now, Mozart most definitely is easier than Brahms. I've had older people (mostly people who didn't know quite as much about music as they thought they did) say exactly that to me - 'ah, you want to conduct Mozart because you think it is easy, you don't realise how hard it is' and I wish now that I'd resisted that more vigorously. I should have said: it's precisely because I appreciate what makes it hard that I can do it.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Rocking the boat vs being too passive

A common but to me unnatural situation in opera houses is what the Germans call 'Nachdirigate' - conductors taking over a piece midway through a run of performances after the busier or more expensive big-name conductor leaves to go and do something else. It's actually a very good thing for young conductors (or repetiteurs wanting to get into doing more conducting) because it increases the opportunities available to the less experienced of us who aren't yet getting offered our own productions, so I'm not complaining. But the trouble with it is that conductors in this situation do not generally get to rehearse with the orchestra and will have limited (if any) time to rehearse with the singers, so they can't really come in and do everything differently from the person they're taking over from. Some people would argue they shouldn't do anything differently - same tempos, same beat patterns, same fermatas. Most people would say there's some room to make it your own but few people, I think, would suggest you can be as free in this situation as you could with your own production.

Suppose you're the conductor taking a musical rehearsal (accompanied by piano) with singers who have done 6 performances of a piece and you're taking over for the last two. Well, first of all, you're lucky to be working in a house that affords you this luxury. But are you, really? What is the rehearsal for? The singers know what they're doing, they have done it enough to have got used to doing the piece a certain way, they have sung it into their voices at your colleague's tempos and while they should be professional enough to cope with small deviations, they will be unlikely to give performances as assured as usual if they are too focused on having to change everything. Remember that anything you change is going to be new for the orchestra as well and they may also be hard to coax into anything very different.

So how far are you going to try to pull the singers in a different direction? Do you give them a whole load of new ideas about how to sing the role, on the basis that they may need an injection of fresh thought to get back to the level of inspiration they felt before they got into a routine? Or do you take the view that if it ain't broke don't fix it?

There are arguments both ways but I think one thing is clear: you should only say something if you have something to say. I think if you have something new to offer and have a sound musical or dramatic reason for persuading a singer to change their interpretation, there's no reason not to throw it out. They will say if they find it too difficult to change at this stage (or don't agree). But it's a big mistake to start trying to change things for the sake of putting your own stamp on something. That's just as true with something you're conducting from the beginning as with a takeover situation: meddling for the sake of it is never a good idea. One sometimes sees that conductors feel they have to say something or people will feel they're being passive; if they don't specify, they seem to worry, they will seem not to care on way or the other.

The trouble is that there is some truth in this. Really strong musicians with a very clear sense of how the music should go probably won't agree with every aspect of someone else's interpretation. They probably will see things differently and will not feel comfortable doing it a way that doesn't fit their conception. Musicians who are not quite as brilliant - or perhaps not quite as experienced - may have figured out that the conductors who impress the most are the ones who come in and instantly know what they want to change, but they may not (yet) have figured out enough about the music they're conducting to know what needs changing. So they fiddle about so as to look more assured than they really are. It might even be a good career strategy; it would be easy to say that everyone sees straight through it but actually I'm not sure that's even always true. But of course it's not a very honest way to make music.

Suppose you're the conductor taking a musical rehearsal (accompanied by piano) with singers who have done 6 performances of a piece and you're taking over for the last two. Well, first of all, you're lucky to be working in a house that affords you this luxury. But are you, really? What is the rehearsal for? The singers know what they're doing, they have done it enough to have got used to doing the piece a certain way, they have sung it into their voices at your colleague's tempos and while they should be professional enough to cope with small deviations, they will be unlikely to give performances as assured as usual if they are too focused on having to change everything. Remember that anything you change is going to be new for the orchestra as well and they may also be hard to coax into anything very different.

So how far are you going to try to pull the singers in a different direction? Do you give them a whole load of new ideas about how to sing the role, on the basis that they may need an injection of fresh thought to get back to the level of inspiration they felt before they got into a routine? Or do you take the view that if it ain't broke don't fix it?

There are arguments both ways but I think one thing is clear: you should only say something if you have something to say. I think if you have something new to offer and have a sound musical or dramatic reason for persuading a singer to change their interpretation, there's no reason not to throw it out. They will say if they find it too difficult to change at this stage (or don't agree). But it's a big mistake to start trying to change things for the sake of putting your own stamp on something. That's just as true with something you're conducting from the beginning as with a takeover situation: meddling for the sake of it is never a good idea. One sometimes sees that conductors feel they have to say something or people will feel they're being passive; if they don't specify, they seem to worry, they will seem not to care on way or the other.

The trouble is that there is some truth in this. Really strong musicians with a very clear sense of how the music should go probably won't agree with every aspect of someone else's interpretation. They probably will see things differently and will not feel comfortable doing it a way that doesn't fit their conception. Musicians who are not quite as brilliant - or perhaps not quite as experienced - may have figured out that the conductors who impress the most are the ones who come in and instantly know what they want to change, but they may not (yet) have figured out enough about the music they're conducting to know what needs changing. So they fiddle about so as to look more assured than they really are. It might even be a good career strategy; it would be easy to say that everyone sees straight through it but actually I'm not sure that's even always true. But of course it's not a very honest way to make music.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)