I get annoyed when conductors hold up two or four fingers as they start beating a passage to let me know whether they’re beating the time in halves or quarters. If you conduct clearly it’s obvious. If you don’t then by the time I see your fingers and process what it means I’ve probably gone double or half speed already. It reminds me of the road signs in Dover (a port in south-east England): for about a mile after you drive off the ferry they are telling you, in four languages, to ‘Drive on left’. How many accidents do they reckon this saves? If you haven’t figured this out by the time you’ve driven a mile, it’s probably a bit late, no?

stage orchestral

what goes on in the mind of an opera house musician?

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

How not to phrase

My current obsession is phrasing. I hardly ever hear it done the way I think it should be. Here are some of the things people seem to think.

- Every time you see a slur or phrase mark, you have to put a big accent at the beginning of it. This is especially true if you are a string player taking a down-bow.

- When you have two slurred notes, you always have to do a massive diminuendo from the first to the second, and the second should be very short.

- You should never make one long phrase when you can make four shorter ones, and you should emphasise this by making the last note of every phrase very short.

- If you have a syncopation that accentuates a weak part of the bar you should emphasise this by playing the strong beat beforehand very weakly and then putting a massive accent on the syncopated note.

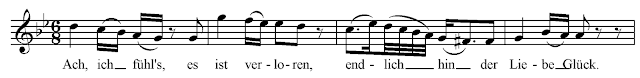

This is obviously all complete nonsense. Instrumentalists should think of how their line would look if it belonged to a singer. Consider the first line of Pamina’s aria, ‘Ach, ich fühl’s’, from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte.

Now this is from memory so I hope you’ll be kind if the last note is really a quarter rather than an eighth, or similar, but this is about how it goes. The German roughly means: ‘Ah, I sense it, it is lost, forever gone love’s happiness’. Pamina sings this aria when Tamino, who has been told by the priests that he will lose Pamina forever if he speaks to her, refuses to answer her, and she takes it as a sign that he no longer loves her.

Here is what you would get if you put this line, without text, in front of most orchestral players:

Now you will not find any soprano in the world who will sing the line like this – at least not one who understands the text or has the remotest clue about how to sing – because it wouldn’t make any sense. It’s one sentence and needs to be phrased with as much line as possible, especially in the slow tempo, so that we understand it as such. And every time instrumentalists see one of these slurs they should remember that it represents one syllable carried over two or more notes. Not even a whole word, let alone a whole phrase. But go into any classical concert and I promise you will hear this kind of phrasing all the time.

I wonder where it comes from. I think it might be bad teachers with nothing to say about the music. It’s a very easy, superficial way of telling the pupil how to ‘improve’ their performance to look down at the page, see a few slurs, accents and syncopations, and tell the poor unsuspecting student ‘you have to emphasise all these things or it’s boring’. After five hours of teaching, often working on music that you might not know all that well, it can be hard to find profound insights. Maybe you are a master of your instrument and good at sorting out people’s technique but not so hot on interpretation. Perhaps your student isn’t really that amazing either, or hasn’t done enough practice, and your motivation is waning. Maybe in some conservatories it is even true that in order to show the jury at your performance exam that you have noticed the slur or the accent you have to parody it. But whatever the reason, it is now incredibly hard to impress on orchestral musicians that it is possible to play the long phrase and let the details speak for themselves.

And even singers, though they might be a bit less inclined to completely bomb a phrase’s meaning to the ground, are also more and more inclined only to sing properly on the strong syllables. I am constantly reminding singers during coachings that the weak syllables have to be looked after as well. It’s very hard to understand a sentence of text where only the strong syllables are projected.

Has anyone got any other ideas where this might come from? Does anyone else find it as annoying and unmusical as I do?

Sunday, January 29, 2012

What's so scary about big heavy books?

Why is it that we feel daunted by the prospect of starting a really long book? We know it will take a long time to finish it, but why does this matter? Surely we don't read for the sake of the sense of achievement at finishing something, we read for the pleasure we get doing it. And most of the time, the more you get into a book the more pleasure you get; it's the first 50 pages that are often the hardest going. So if anything it takes less effort to read one 800-page novel than four of 200 pages each. Yet somehow, in front of the bookshelf, we feel scared of the commitment.

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

How to learn an opera

I'm not entirely sure how many repetiteurs are out there waiting for me to explain to them how to learn a score. But just in case, here is my method. For me it works for anything up to Verdi; for Wagner, R Strauss and 20th-century works I use a slightly different approach which I'll explain another time.

Step 1. Obtain a recording. You'll get a lot more wear out of a good one than out of a budget one you'll want to upgrade in a couple of years so spend whatever you can afford to get the best one you can.

Step 2. Subconscious learning. Leave the music playing whenever possible for the week or two before you start learning; while you're cooking, reading, checking email, eating breakfast. You don't have to listen. Just hear it as often as possible.

Step 3. First crack. Play through the opera, singing all the voice parts as you go. Stop, slow down or repeat as often as you need to.

Step 4. Overview. Play through just the piano reduction without singing. Try not to stop too much.

Step 5. Familiarisation. You're now at the stage where you have enough scaffolding for information to adhere to. Read through the libretto, and a translation of it if you don't speak the language. (If you sort of speak it and reckon you can understand most of what's going on, read through a translation. You need to understand every word.)

Step 6. Listen through to your recording while following your score. This is a crucial stage and if you do this properly, really reading the music as it goes, and you've followed the previous steps, then by the time you get through this step you should be pretty much ready.

Step 7. Go through the piece one more time focusing now on singing the parts. Accompany yourself sketchily but don't be afraid to reduce to just harmony or even just a bass line, but make sure you sing all the text.

Step 8. Play through the whole thing again, trying to focus equally on singing and playing but prioritising playing if you can't always do both. (This step is a luxury. Usually by now rehearsals have started and I have to start learning the next piece.)

Not counting steps 1+2, this plan very roughly means that you should allow learning of time of 6 times the duration of the opera (this is allowing for step 3 to take twice as long as if you played straight through). Remember that memory takes time to set so you'll be more efficient if you spread this process over 2-3 weeks than if you try to cram it into the three days before rehearsals start. But turbo learning in an emergency is something one has to do sometimes and the plan still works.

Step 1. Obtain a recording. You'll get a lot more wear out of a good one than out of a budget one you'll want to upgrade in a couple of years so spend whatever you can afford to get the best one you can.

Step 2. Subconscious learning. Leave the music playing whenever possible for the week or two before you start learning; while you're cooking, reading, checking email, eating breakfast. You don't have to listen. Just hear it as often as possible.

Step 3. First crack. Play through the opera, singing all the voice parts as you go. Stop, slow down or repeat as often as you need to.

Step 4. Overview. Play through just the piano reduction without singing. Try not to stop too much.

Step 5. Familiarisation. You're now at the stage where you have enough scaffolding for information to adhere to. Read through the libretto, and a translation of it if you don't speak the language. (If you sort of speak it and reckon you can understand most of what's going on, read through a translation. You need to understand every word.)

Step 6. Listen through to your recording while following your score. This is a crucial stage and if you do this properly, really reading the music as it goes, and you've followed the previous steps, then by the time you get through this step you should be pretty much ready.

Step 7. Go through the piece one more time focusing now on singing the parts. Accompany yourself sketchily but don't be afraid to reduce to just harmony or even just a bass line, but make sure you sing all the text.

Step 8. Play through the whole thing again, trying to focus equally on singing and playing but prioritising playing if you can't always do both. (This step is a luxury. Usually by now rehearsals have started and I have to start learning the next piece.)

Not counting steps 1+2, this plan very roughly means that you should allow learning of time of 6 times the duration of the opera (this is allowing for step 3 to take twice as long as if you played straight through). Remember that memory takes time to set so you'll be more efficient if you spread this process over 2-3 weeks than if you try to cram it into the three days before rehearsals start. But turbo learning in an emergency is something one has to do sometimes and the plan still works.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

How to wind an orchestra up in a first rehearsal

Actually there are quite a few ways. One really good one, though, is to stop every eleven bars to say something uninspiring about playing the staccatos shorter, starting the crescendos quieter, using softer sticks for the timpani, or any of the other dozens of things that good musicians will figure out for themselves once they've got a bit of an overview.

You do this mostly to cover up for having stopped because it fell apart due to your lack of clarity; not daring to draw attention to this by either apologising or attempting to blame the players, you try to act like you stopped for something else. Already made uncomfortable by this failure, you start to obsess that the players are watching you like hawks and noticing your ineptitude with the grim relish of a connoisseur sending back corked wine, which they are. Never all that secure about your conducting to begin with, this latest confirmation of your self-doubt makes you unable to do the simplest thing; you can't give a clear upbeat and even if you do you aren't sure the tempo you hear is the one you meant, or if the one you meant was even right anyway, and maybe the orchestra misread you because they have a different tempo in their heads, and maybe in fact they're right and you were imagining it wrong, and all this self-analysis when you should be concentrating on listening to the rehearsal makes you lose concentration and you realise you've had to stop again, but you were so busy thinking about what had gone wrong with the upbeat that you haven't been listening and can't think of anything to correct, and you look down at the score trying to find a commonplace mistake that you weren't sure if it was wrong but somebody probably did play it wrong somewhere and even if they didn't they might do next time, and on you go, making it worse and worse. And you can practically hear them asking each other, 'why is this guy conducting us', and well, hell, why wouldn't you hear it, everyone else can. As you pick a place to start two bars further forward than the previous time so it feels like you're making progress and count out the measures for the orchestra, you see out of the corner of your eye that the normally docile woodwind players are exchanging looks, and you try to tell yourself it's a private joke that has nothing to do with this rehearsal but you remember your own days playing in an orchestra and you know that isn't true.

Well, we've all been there, conductors and players alike, and knowing what it feels like from the other side I have more sympathy than it sounds like just now. But although the reasons outlined above account for most of the first-rehearsal stopping, and actually most conductors doing this know perfectly well that the most productive thing would be to crash through with only the most critical stops, they do still sometimes forget that and manage to convince themselves that talking to the orchestra is useful. Orchestral players know that it isn't. And it certainly isn't when the players haven't got any idea of the music yet. Why not?

It seems to me that we are wired up to learn music (and other things) in a way that resembles the appearance of a Google Maps image loading on a slow smartphone. Very blurry at first, then kind of pixellated with some patches of green visible, then suddenly the hit of satisfaction as the image rights itself and sharpens up. And you know also how while it's loading the phone is apt to freeze if you try to drag the map an inch or two to the side, but once it's got the area loaded into the memory you can drag, zoom in, zoom out, search for the closest place to buy charcoal or display all the bus stops served by night buses and the phone will keep up with your impatient fingers, gliding effortlessly through hyperinformatic space. (If you're reading this in a couple of years' time and can't believe people used to struggle through life with technology this deficient, imagine how I feel.)

So, but this is what learning music is like. You can't find the shortest route from ATM to off-licence until you've got the whole picture loaded. It is most especially not like pictures used to download in early versions of Netscape c. 1992, a beautifully defined strip of sky, followed by a perfect treetop, eventually a few strands of hair at the top of the tallest person in the picture's head, and an eternity later, legs, feet, ground. (Probably what changed this is that the men writing the software for these browsers thought about the kind of pictures they most often wanted to look at on the internet and realised it was not in their interests to spend their then-precious bandwidth allowances on the detailed image of people's head-tops before you knew whether you liked what you were getting much lower down in the picture.) Music cannot be learned this way. You can only get to the detail by going through the overview; you just need to play something through a few times, eventually things start to click into place. Conductors who understand this and just let you play get results much faster.

It's getting late and I have another rehearsal to look forward to tomorrow morning so I have to stop writing pretty soon but just one further thought. I'm sure you know what I'm talking about whether or not you're a musician; we've all experienced that feeling of not really knowing enough about something to make any connections, the sense that reading another article on the same topic will just double your overall understanding of it from nothing to nothing, the questioning whether you will every really actually get the thing enough to really be comfortable with it like other people seem to be. But equally you will know what I mean that at some point things just click somehow and it all does make sense, and not only does the next thing someone tells you about the topic seem to make complete sense, but it connects with something else you remember hearing about it that at the time you thought wasn't going in at all because it didn't really seem to mean anything, and then someone asks you to explain it to them and all of a sudden you find that you are doing that and sounding rather well-informed.

Well but then the brain must be able to store an incredible amount of not-yet-connected pre-knowledge long before it's in a position to make sense of it. That feeling you get when you listen to a piece of music for the twelfth time and you can hear what phrase is going to come next before it does, even if someone turned the player off, it only comes after quite a few playings. After the first time - with hard music, anyway - you would not be able to complete any phrases like that, or remember any of how the music goes 15 minutes after listening to it. You feel just as if you'd never heard it at all. And yet something has just remained, because you are still one-twelfth of the way to the point where you will be hearing it, and after the second time - when you still may not be able to remember how any of it goes - you will be one-sixth. I find this incredible. I do not find it difficult to accept that my brain can store a lot of information that I have access to and can marshall in a conscious way. But that my brain can also be storing a whole load of information that I can't get at and can't in any way sense is there, but that will at some point with the right sensory inputs be movable into this active conscious domain - I find that amazing.

You do this mostly to cover up for having stopped because it fell apart due to your lack of clarity; not daring to draw attention to this by either apologising or attempting to blame the players, you try to act like you stopped for something else. Already made uncomfortable by this failure, you start to obsess that the players are watching you like hawks and noticing your ineptitude with the grim relish of a connoisseur sending back corked wine, which they are. Never all that secure about your conducting to begin with, this latest confirmation of your self-doubt makes you unable to do the simplest thing; you can't give a clear upbeat and even if you do you aren't sure the tempo you hear is the one you meant, or if the one you meant was even right anyway, and maybe the orchestra misread you because they have a different tempo in their heads, and maybe in fact they're right and you were imagining it wrong, and all this self-analysis when you should be concentrating on listening to the rehearsal makes you lose concentration and you realise you've had to stop again, but you were so busy thinking about what had gone wrong with the upbeat that you haven't been listening and can't think of anything to correct, and you look down at the score trying to find a commonplace mistake that you weren't sure if it was wrong but somebody probably did play it wrong somewhere and even if they didn't they might do next time, and on you go, making it worse and worse. And you can practically hear them asking each other, 'why is this guy conducting us', and well, hell, why wouldn't you hear it, everyone else can. As you pick a place to start two bars further forward than the previous time so it feels like you're making progress and count out the measures for the orchestra, you see out of the corner of your eye that the normally docile woodwind players are exchanging looks, and you try to tell yourself it's a private joke that has nothing to do with this rehearsal but you remember your own days playing in an orchestra and you know that isn't true.

Well, we've all been there, conductors and players alike, and knowing what it feels like from the other side I have more sympathy than it sounds like just now. But although the reasons outlined above account for most of the first-rehearsal stopping, and actually most conductors doing this know perfectly well that the most productive thing would be to crash through with only the most critical stops, they do still sometimes forget that and manage to convince themselves that talking to the orchestra is useful. Orchestral players know that it isn't. And it certainly isn't when the players haven't got any idea of the music yet. Why not?

It seems to me that we are wired up to learn music (and other things) in a way that resembles the appearance of a Google Maps image loading on a slow smartphone. Very blurry at first, then kind of pixellated with some patches of green visible, then suddenly the hit of satisfaction as the image rights itself and sharpens up. And you know also how while it's loading the phone is apt to freeze if you try to drag the map an inch or two to the side, but once it's got the area loaded into the memory you can drag, zoom in, zoom out, search for the closest place to buy charcoal or display all the bus stops served by night buses and the phone will keep up with your impatient fingers, gliding effortlessly through hyperinformatic space. (If you're reading this in a couple of years' time and can't believe people used to struggle through life with technology this deficient, imagine how I feel.)

So, but this is what learning music is like. You can't find the shortest route from ATM to off-licence until you've got the whole picture loaded. It is most especially not like pictures used to download in early versions of Netscape c. 1992, a beautifully defined strip of sky, followed by a perfect treetop, eventually a few strands of hair at the top of the tallest person in the picture's head, and an eternity later, legs, feet, ground. (Probably what changed this is that the men writing the software for these browsers thought about the kind of pictures they most often wanted to look at on the internet and realised it was not in their interests to spend their then-precious bandwidth allowances on the detailed image of people's head-tops before you knew whether you liked what you were getting much lower down in the picture.) Music cannot be learned this way. You can only get to the detail by going through the overview; you just need to play something through a few times, eventually things start to click into place. Conductors who understand this and just let you play get results much faster.

It's getting late and I have another rehearsal to look forward to tomorrow morning so I have to stop writing pretty soon but just one further thought. I'm sure you know what I'm talking about whether or not you're a musician; we've all experienced that feeling of not really knowing enough about something to make any connections, the sense that reading another article on the same topic will just double your overall understanding of it from nothing to nothing, the questioning whether you will every really actually get the thing enough to really be comfortable with it like other people seem to be. But equally you will know what I mean that at some point things just click somehow and it all does make sense, and not only does the next thing someone tells you about the topic seem to make complete sense, but it connects with something else you remember hearing about it that at the time you thought wasn't going in at all because it didn't really seem to mean anything, and then someone asks you to explain it to them and all of a sudden you find that you are doing that and sounding rather well-informed.

Well but then the brain must be able to store an incredible amount of not-yet-connected pre-knowledge long before it's in a position to make sense of it. That feeling you get when you listen to a piece of music for the twelfth time and you can hear what phrase is going to come next before it does, even if someone turned the player off, it only comes after quite a few playings. After the first time - with hard music, anyway - you would not be able to complete any phrases like that, or remember any of how the music goes 15 minutes after listening to it. You feel just as if you'd never heard it at all. And yet something has just remained, because you are still one-twelfth of the way to the point where you will be hearing it, and after the second time - when you still may not be able to remember how any of it goes - you will be one-sixth. I find this incredible. I do not find it difficult to accept that my brain can store a lot of information that I have access to and can marshall in a conscious way. But that my brain can also be storing a whole load of information that I can't get at and can't in any way sense is there, but that will at some point with the right sensory inputs be movable into this active conscious domain - I find that amazing.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Composers: show some respect

When I write music I am fantastically careful about the preparation of parts. I try extremely hard to make sure that everything is prepared and presented so well as to make life as easy as possible for anyone who will be learning, playing or conducting my music. Why? Firstly on selfish grounds, because they probably won't have infinite preparation time and so any time they spend deciphering unclear notation takes away from learning to play my music better and will mean a less good performance. Secondly out of respect for the players, to whom I owe a great debt of gratitude that they have chosen my music ahead of the squillions of other pieces out there, and the least I can do to repay them is to give them something legible to play from. Thirdly out of pride that I was taught how to produce properly notated music and am able to do it and I don't want anyone to think I'm one of the people I'm about to moan about. Obviously despite all one's efforts the occasional mistake creeps in. All the more reason to try harder; without one's best efforts the number of mistakes will rise astronomically.

I get really impatient when I find myself learning music by other people who haven't taken the same care that I would expect of myself. This probably isn't the place to try to prepare a notation handbook and so I'm not going to attempt an exhaustive list of everything you ought to know if you're preparing music for performers, though such handbooks do exist and it would be nice if composers who prepare their own materials consulted one from time to time. But just so you know what I'm talking about here are a few examples.

1. Cautionary accidentals. Not providing these is the single biggest 'f*** you' to performers that composers are guilty of. If you have a G# before the barline and a G natural after the barline then the natural sign is NOT optional. If in doubt, put one. It's also not patronising to restate an accidental towards the end of the bar that we've forgotten since the beginning because it's so chromatic in between. Better too much information than too little.

2. 8va lines. Please remember: the number of objects the eye can instantly see and know the number without counting is five. Throw some matches on the floor and try it. After five you have to count. Reading music there isn't time to do this. Do not use more than five leger lines.

3. Consistent placing of staves on the page. In a given section or ensemble, if I am following the part of Bob the Builder and I turn the page, his part should continue at the same vertical point on the page. If that means having an empty stave for Tinky Winky, who has 5 bars' rest so doesn't sing anything on that system, that's fine. Constantly juggling the parts so that you have to keep moving the eye up and down is a complete nightmare. This isn't a hard and fast rule; you have to be intelligent about it. But if we are talking about an ensemble that lasts, say 50 bars, and involves 8 singers, hold the number of staves constant. If it's 200 bars and 2 of the singers only have 3 lines then you might not. This applies more to vocal scores, for full scores you probably wouldn't use empty staves.

4. If you don't use computers and produce handwritten scores, that is fine on principle. But engraving music by hand is an art. It is highly skilled expert work for a professional and if you are a career composer then you probably haven't had time to learn it properly. Not by most of the evidence available, anyway. Give it to someone who knows what they're doing. If you must do it yourself, do not take shortcuts. Leger lines must be perfectly spaced. Accidentals in chords should be in the right order. Spacing of rhythms within the bar should be sensible (this is also a very frequent problem with computer-produced scores). Sharps, flats and naturals should look unmistakeably different from one another. Noteheads should be big enough to read. Stem lengths should be constant and the stems should be straight; so should beams joining eighth-notes and smaller. Text should be legible and the music should be given extra space to accommodate text rather than the text being squashed. If at all possible the text should be in just the original language but if you must give a singing translation please be consistent about which way round the languages appear.

This may all seem obvious but you would be amazed how consistently these rules are broken by very well-respected and well-known composers. The most infuriating thing as a repetiteur is that the orchestral score and parts are almost always produced by computer and are legible, but then the vocal score is done by hand - do repetiteurs and singers just not complain loudly enough? I find it mildly scandalous that we should have to sit there counting spidery leger lines while the better-unionised orchestral players get computer-prepared parts.

Computers are not the solution to everything, of course, and they bring their dangers too. You can always tell an amateur whose music is mostly brought to life by the playback algorithm of his notation software by notation that is technically correct and perfectly readable to a computer, but for a human brain much harder to read - see rules #1 and #2 above, for starters.

That said there are also aspects of how the mind processes information that are more computational than hand-written scores give them credit for. Most of the things I mention in point #4 cause difficulties not because it isn't obvious what's meant - of course we still know what four sixteenth-notes are when the beams joining them aren't quite straight. But the mind is much better than we realise at processing information subconsciously and when things are neatly, predictably and mathematically presented it can get on with this without having to take up too much conscious thinking power. When things are comprehensible but require the brain to engage a conscious analysis circuit, it makes it much harder.

I could go on and on but I think you get the idea. When I see the parts that we are mostly presented with for new music my usual first reaction is: is he not ashamed? Do his cheeks not burn with the disgrace of such unprofessional work? Does he not recoil in fear of what his colleagues will think of him for producing this? And then as I am forced to accept that the composer must in fact be sleeping perfectly well or he would do something about it, I think: well, sod you, then. If you cared that we play the right notes rather than just making it up you would produce decent parts, so perhaps you just don't. I feel insulted that somebody who probably walked of with tens of thousands of euros for this is happy to let me struggle along reading this spider scrawl.

And then in the end, because I'm a professional and a perfectionist and a soft touch, I sit there sweating it out and learn the music properly all the same and I resolve never to play anything by that composer again.

I get really impatient when I find myself learning music by other people who haven't taken the same care that I would expect of myself. This probably isn't the place to try to prepare a notation handbook and so I'm not going to attempt an exhaustive list of everything you ought to know if you're preparing music for performers, though such handbooks do exist and it would be nice if composers who prepare their own materials consulted one from time to time. But just so you know what I'm talking about here are a few examples.

1. Cautionary accidentals. Not providing these is the single biggest 'f*** you' to performers that composers are guilty of. If you have a G# before the barline and a G natural after the barline then the natural sign is NOT optional. If in doubt, put one. It's also not patronising to restate an accidental towards the end of the bar that we've forgotten since the beginning because it's so chromatic in between. Better too much information than too little.

2. 8va lines. Please remember: the number of objects the eye can instantly see and know the number without counting is five. Throw some matches on the floor and try it. After five you have to count. Reading music there isn't time to do this. Do not use more than five leger lines.

3. Consistent placing of staves on the page. In a given section or ensemble, if I am following the part of Bob the Builder and I turn the page, his part should continue at the same vertical point on the page. If that means having an empty stave for Tinky Winky, who has 5 bars' rest so doesn't sing anything on that system, that's fine. Constantly juggling the parts so that you have to keep moving the eye up and down is a complete nightmare. This isn't a hard and fast rule; you have to be intelligent about it. But if we are talking about an ensemble that lasts, say 50 bars, and involves 8 singers, hold the number of staves constant. If it's 200 bars and 2 of the singers only have 3 lines then you might not. This applies more to vocal scores, for full scores you probably wouldn't use empty staves.

4. If you don't use computers and produce handwritten scores, that is fine on principle. But engraving music by hand is an art. It is highly skilled expert work for a professional and if you are a career composer then you probably haven't had time to learn it properly. Not by most of the evidence available, anyway. Give it to someone who knows what they're doing. If you must do it yourself, do not take shortcuts. Leger lines must be perfectly spaced. Accidentals in chords should be in the right order. Spacing of rhythms within the bar should be sensible (this is also a very frequent problem with computer-produced scores). Sharps, flats and naturals should look unmistakeably different from one another. Noteheads should be big enough to read. Stem lengths should be constant and the stems should be straight; so should beams joining eighth-notes and smaller. Text should be legible and the music should be given extra space to accommodate text rather than the text being squashed. If at all possible the text should be in just the original language but if you must give a singing translation please be consistent about which way round the languages appear.

This may all seem obvious but you would be amazed how consistently these rules are broken by very well-respected and well-known composers. The most infuriating thing as a repetiteur is that the orchestral score and parts are almost always produced by computer and are legible, but then the vocal score is done by hand - do repetiteurs and singers just not complain loudly enough? I find it mildly scandalous that we should have to sit there counting spidery leger lines while the better-unionised orchestral players get computer-prepared parts.

Computers are not the solution to everything, of course, and they bring their dangers too. You can always tell an amateur whose music is mostly brought to life by the playback algorithm of his notation software by notation that is technically correct and perfectly readable to a computer, but for a human brain much harder to read - see rules #1 and #2 above, for starters.

That said there are also aspects of how the mind processes information that are more computational than hand-written scores give them credit for. Most of the things I mention in point #4 cause difficulties not because it isn't obvious what's meant - of course we still know what four sixteenth-notes are when the beams joining them aren't quite straight. But the mind is much better than we realise at processing information subconsciously and when things are neatly, predictably and mathematically presented it can get on with this without having to take up too much conscious thinking power. When things are comprehensible but require the brain to engage a conscious analysis circuit, it makes it much harder.

I could go on and on but I think you get the idea. When I see the parts that we are mostly presented with for new music my usual first reaction is: is he not ashamed? Do his cheeks not burn with the disgrace of such unprofessional work? Does he not recoil in fear of what his colleagues will think of him for producing this? And then as I am forced to accept that the composer must in fact be sleeping perfectly well or he would do something about it, I think: well, sod you, then. If you cared that we play the right notes rather than just making it up you would produce decent parts, so perhaps you just don't. I feel insulted that somebody who probably walked of with tens of thousands of euros for this is happy to let me struggle along reading this spider scrawl.

And then in the end, because I'm a professional and a perfectionist and a soft touch, I sit there sweating it out and learn the music properly all the same and I resolve never to play anything by that composer again.

Monday, October 17, 2011

Lost in translation

Why do so many expats have two greeting messages, in their native and adopted languages, when you ring them and get their voicemail? Do they worry that people who don't know what 'please leave a message' is in German won't know what to do?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)